Dear Neighbors,

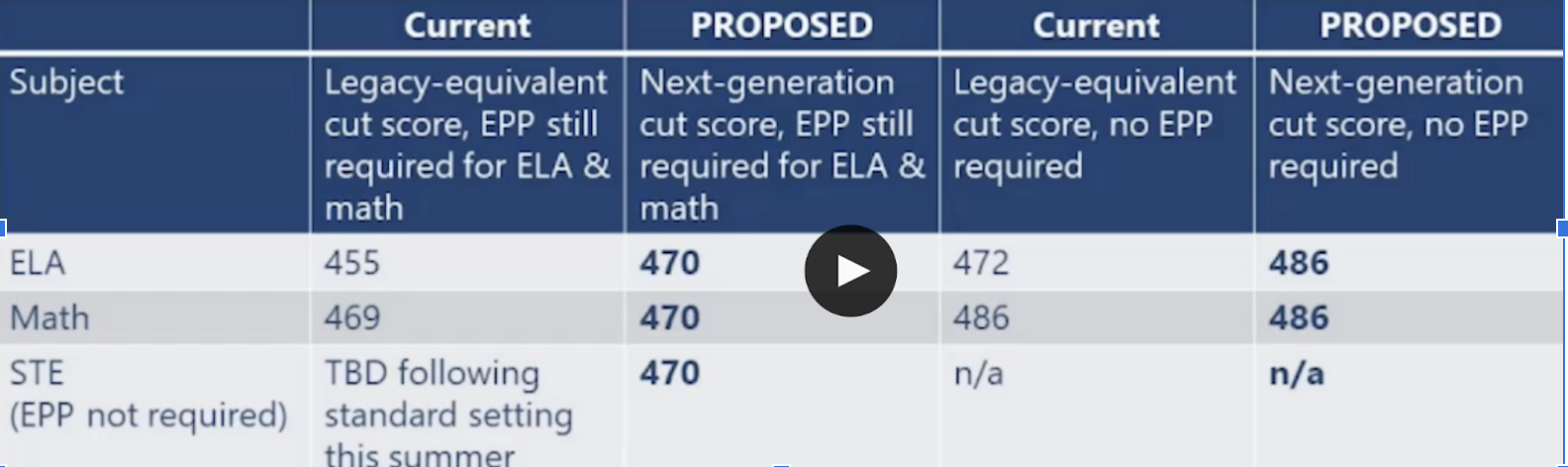

In August, the Massachusetts Board of Elementary and Secondary Education voted to raise the minimum score that this year’s freshman class, and classes following, will have to attain on the MCAS test in order to graduate. And against Commissioner Riley’s recommendation, they voted to increase the passing score further for classes starting in 2030. They also voted, against Commissioner Riley’s recommendation, to increase the passing score further for classes starting in 2030.

The three members chosen by students, teachers and labor voted against both proposals. The eight members who were chosen by Gov. Baker alone voted to make the changes. Shockingly, educators and school committee members are prohibited by law from serving on the Board. This is unlike boards that regulate other professions. Rep. Garballey filed legislation to add two teachers; Rep. Ultrino filed a bill to add a school committee member. These have not been approved by the Education Committee.

In May, Sen. Jo Comerford, Rep. Jim Hawkins and I wrote a letter to the Board asking them not to approve the change. In just a few days, 98 representatives and senators (half the legislature) signed it. As we wrote, "It was easy to collect the sign ons from our colleagues because long-standing issues with the MCAS test are widespread – hearing urgent calls for help and action, as we do, from the people we represent."

The public comment, like ours, was over 98% in opposition to the higher requirements. 225 comments opposed to the proposed changes, and 4 emails were in support. Our comments and those of others focused on harm to English learners, students with disabilities, low-income students, and Black and Latino students. The comments also argued that there would be more time spent on test prep instead of meaningful learning, more pressure on students and teachers who were already suffering from the stress of the pandemic, and an increase in dropouts.

Sen. Comerford, Rep. Hawkins and I returned from our vacations to testify at the August meeting. My testimony, focusing on the probable damage to English Learners, is at the end of the email and here. You can watch our testimony here; it starts at 3:19; I'm at 7:47. Coverage included the Somerville Times, Fall River Reporter and other local newspapers.

Our testimony was consistent with the recent guidance from the federal government, which asks states "to reduce the high stakes of assessments in such State decisions as graduation...requirements." The federal department encourages states to emphasize "the original intended uses of statewide annual assessments: to provide comparable data to identify outcome gaps," inform parents, and prioritize resources. In fact, most states have eliminated tests as a graduation requirement; only 11 still retain it.

Many have questioned the timing of raising the passing score at a time when so many students, teachers, families and schools are still suffering effects of the pandemic. Commonwealth reported that "Reading and math scores plummet amid pandemic." The Globe used the same language: "MCAS scores plummet during the pandemic." In a poll last year, 55% of parents reported a negative impact of the year on their child's mental or emotional health.

Why would the board do this at this time? One possible answer is that in January there will be a new governor, with the power to appoint a new Secretary of Education and to fill board vacancies.

Testing has not reduced gaps. Max Larkin of WBUR recently posted a comparison of scores by school, compared with the number of low-income students.

Four years ago, I wrote a report for a Senate committee I chaired on accountability. The Massachusetts Achievement Gap Act of 2010 had dramatically raised the high stakes for districts to improve test scores, I found that the results on the National Assessment of Educational Progress (for which students can't prep) showed gaps "increased in eight out of twelve comparisons, decreased in three, and remained unchanged in one."

South Coast Today compared scores in New Bedford and nearby Westport. In New Bedford, 82.5% of students are low income; 25.8 English learners. In Westport, 35.8% are low income and 1.5% ELs. The paper found that the average Westport student would easily surpass the new graduation requirement; most New Bedford students would fail.

Maybe you'd like to try your hand at the 10th grade sample tests and scoring guide. I found it instructive.

What will happen for students who fail in 10th grade? Here's one answer: JFYNetWorks recently announced that the sample test questions for 2022 had been released. The image on the right was from an email this summer, saying they are excited that they now know exactly which standards will be on the tests. Now they can focus on those and not others. This answers the question so many students ask: Will this be on the test? JFYNetWorks curriculum includes practice tests and test-taking strategies, all on-line. Over a hundred Massachusetts schools use their program through an appropriation of $875,000 from the state. Just asking: Do we need more on-line instruction?

My testimony is below my signature. I'd like to hear your thoughts.

Stay well, and stay in touch,

Pat Jehlen

Testimony to Mass. Board of Elementary and Secondary Education, August 15, 2022

In opposition to raising the passing score for MCAS

Raising the passing score for English MCAS will harm children who are English Learners (ELs). This is the fastest growing group of students in our schools: and is now over 100,000 or 11% of all students.

These students will be the most affected by raising the English passing score because they don’t yet read and write English fluently. They can have bright futures as important members of our community and contributors to our economy if they can just get a high school diploma.

In the pre-pandemic class of 2020, only about half of English learners passed both the MCAS English and math tests as sophomores. Raising the English passing score will cause more of them to fail.

What happens to students who don’t pass in 10th grade? They’re more likely to drop out, as 2010 research by Prof. Papay and other s confirmed. Indeed, ELs are almost four times more likely to drop out than the average. (5.8% vs. 1.5%).

And what happens to young people who don’t graduate from high school?

Without a diploma, or a GED which is also especially difficult for English Learners, young people can’t get into higher education, including community college. They can’t get into most apprenticeship programs. Even a GED probably won’t get them into the military. These are all opportunities for upward mobility and long-term economic success. They are all unavailable to students who don’t graduate.

For those students who persist and stay in school, raising the score will not help them learn English faster. They will just spend more time on test prep and strategies for getting around MCAS – not the kind of communications skills they need; not internships or career exploration; and not the kind of applied skills business leaders say they need. [In a poll by the Mass. Business Alliance for Education, which nevertheless advocated raising the passing score.]

English Learners have overcome incredible, often life-threatening, obstacles to get here. They continue to face daunting obstacles just to get to school. Please don’t raise this barrier to their success.

Note after the meeting: Commissioner Matt Hills said the number of students failing under the new standards would be “de minimis” but no one said how many that would be. The next day Commissioner Martin West said that they expect 3300 additional students to fail the MCAS under the new standards.